Uniquely Yours: Commissioned Art

A few years ago, I commissioned a painting.

A few years ago, I commissioned a painting.

“You commissioned a painting?” One might ask incredulously, especially if they saw my bank statement. It wasn’t the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, but yes, I commissioned a painting—a folk art piece by New York artist Sara Pulver, whose work can be found on Etsy, among other places.

At the time, Pulver was doing a series called “Cat and Crow,” which featured a pointy-eared, red cat and an oversized black crow doing various things together—bicycling, singing, playing guitar, etc.—sometimes accompanied by a Martian friend called Alien.

My sister, Theresa, collects Pulver’s work. She and I had recently returned from a vacation in New Mexico, and with the holidays looming, I wondered if perhaps Pulver could paint Cat and Crow in the Land of Enchantment for Theresa’s Christmas present.

I sent the artist an email, explaining what I envisioned and asking if she did commissions. She responded, saying she did and would be happy to do one for me. We agreed on a price and in a couple of weeks, an original painting of Cat and Crow in New Mexico arrived on my doorstep.

Commissioning artwork can be that simple: a few email exchanges, a check in the mail and —voilà!— you’re an art collector, but there are some things you should know before you start commissioning objets d’art.

The first thing is, no matter what type of artwork you’re considering, you need to come up with a basic idea. After all, you’ll have to tell the artist what you want, and he or she is an artist, not a mind reader. You could also sketch out your idea, tear pictures from magazines or peruse the Internet for things that appeal to you.

“They should have some idea of the style of art that they like, and make a good connection with the artist and interview the artist,” said Robin Poteet, a Roanoke watercolor artist and muralist. “And get a good idea of price. [You] may not be able to get a firm number, but the better the communication the better the end result is going to be.”

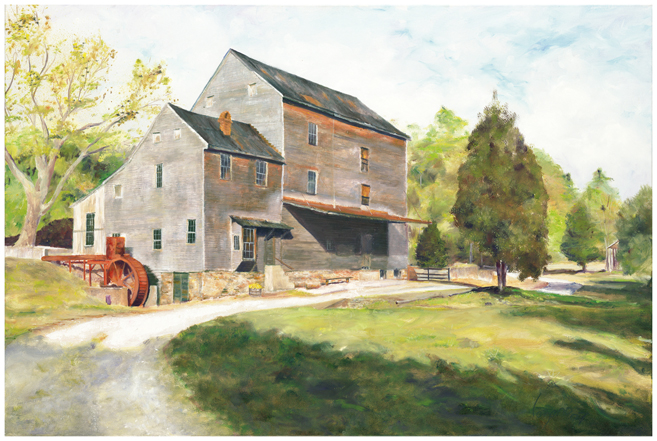

Poteet has done a number of commissions, including house portraits. She has also created elaborate sketchbooks of her vacations to Europe, and co-authored one, “Bonny Views of Ireland,” with Virginia artist Vera Dickerson in 2009.

Poteet has done a number of commissions, including house portraits. She has also created elaborate sketchbooks of her vacations to Europe, and co-authored one, “Bonny Views of Ireland,” with Virginia artist Vera Dickerson in 2009.

“The sketchbook … is what I’d love to do as commission work for travelers,” she said.

On that line, there is no point in asking an artist to do something that is not his or her specialty, or in a style they’re not comfortable doing. “You should be able to research the artist and see if they’ll be a good fit,” said Luis Lozano, a Lynchburg oil painter who has done numerous commissions. “You don’t want Salvador Dali doing a picture of Grandma.”

For Betty Branch, a nationally known sculptor from Roanoke, it’s a matter of staying true to herself, as well as a practical matter. “I think an artist owes that to themselves, to not take on anything that basically is not the thing they love to do,” she said. “You do, occasionally, work outside that frame, but you don’t want to go far outside that frame. Basically, the client is coming to you for what you are known for doing.”

For Betty Branch, a nationally known sculptor from Roanoke, it’s a matter of staying true to herself, as well as a practical matter. “I think an artist owes that to themselves, to not take on anything that basically is not the thing they love to do,” she said. “You do, occasionally, work outside that frame, but you don’t want to go far outside that frame. Basically, the client is coming to you for what you are known for doing.”

Poteet said if asked to do something that is “not really my strength,” she often recommends another artist. “We can certainly attempt to paint in a different manner, but everyone has their own individual style,” she said.

But how do you find an artist in the first place? In short, follow the art. There are many galleries in our area. There are also a number of annual outdoor art festivals, among them Roanoke’s Sidewalk Art Show in June, the Lynchburg Art Festival and Bedford Centerfest in September and Smith Mountain Lake Art Show in October.

At “First Friday”-type events—“2nd Friday” in Bedford— artists open their studios to anybody and everybody. There’s often music and snacks. You get to see local artwork and talk to real, honest-to-goodness artists in an unpretentious setting. If someone’s artwork “speaks” to you, you can strike up a conversation with the artist.

Poteet, who has exhibited her work at both the Lynchburg Art Festival and Sidewalk Art Show, said she’s gotten work this way. “You have the opportunity to talk with people and talk about your work,” she said, “and they might mention, ‘I’ve been to such-andsuch place. Gee, could you do a painting for me, based on this or that, in this size?’”

Area artists also say said clients have found them via the Internet. “It works in a lot of different ways,” said Michael Creed, a Lynchburg craft artist who builds what he calls “functional sculptures,” fanciful desks, chairs, stepladders and other furniture, often in the shape of Betty Branch animals or insects.

This past winter Creed was working on two desks. One was for a Lynchburg woman who had seen his work at area galleries and art festivals, and the second was for a woman in New York City who found him online.

This past winter Creed was working on two desks. One was for a Lynchburg woman who had seen his work at area galleries and art festivals, and the second was for a woman in New York City who found him online.

The New Yorker found him on CustomMade.com, a Bostonbased website that, Creed said, “tries to marry the interests of craft artists and craftsmen with people who need something. It’s huge, there must be a thousand makers on the site.”

CustomMade showcases everything from fine art to fine furniture, and has a “project board,” where people can post a description or picture of a project they’d like done, along with an idea of their budget. Creed said artists “look at the job board and see if there’s anything that we want to express interest in [and] we start a conversation.”

Sometimes people who visit the website see something they like and contact CustomMade to be connected with the artist. “In this circumstance, that’s what happened,” Creed said. “I got picked out of a very large crowd of puppies, you might say.”

The cost of acquiring an original piece of artwork, commissioned or not, runs across the board. It could be significantly less than a hundred bucks or something that might make a Rockefeller shudder. Basically, it all depends on the artist and how complicated the job is.

“The more detailed the work, the more expensive it is,” Lozano said, adding that in the case of portraiture, “Some artists actually charge for hands, because some artists find the hands very difficult to do.”

“The more detailed the work, the more expensive it is,” Lozano said, adding that in the case of portraiture, “Some artists actually charge for hands, because some artists find the hands very difficult to do.”

A commissioned piece by Creed will cost from $3,000 to $30,000. Lozano’s paintings, with subjects ranging from boat and home portraits to scenes from the Lynchburg Batteau Festival, have been commissioned for $500 to $7000, but routinely sell for $1,000 to $3,000.

Poteet said most of her commissions have been in the $250 to $700 range. Her custom sketchbooks start at $300, depending on the number of pages and images.

A bronze sculpture by Branch, whose award-winning work has been exhibited internationally and at such prestigious competitions as the Brookgreen Gardens Invitational in Myrtle Beach, S.C., will cost a hefty $5,000 to $90,000.

The process is long and “enormously hands-on,” Branch said, beginning with sketches and a clay or wax model she makes at her studio in Roanoke’s rail yard district. During this stage, the buyer may make changes.

“When you create sculpture … it’s done in an impermanent form,” Branch explained. “A bronze can come from any form, but if you’re doing a commission, you’re working on materials that are malleable, that can be changed up to the point where the client can say, ‘This is exactly what I want.’”

Once everything pleases both client and artist, the piece goes to a foundry in Baltimore. The casting process may take six months or more, during which Branch travels to Baltimore three times to oversee the work. The whole thing, from idea to sculpture, could take a year.

“It’s very involved and very expensive,” Branch said. “And that’s … why the schedule of payment is so important because that first third pays for the artist’s time and overhead.”

Artists typically require a deposit or design fee, with the balance paid at regular intervals or upon receipt or installation of the item. Some artists offer payment plans or layaway, and some have satisfaction guarantees and return policies.

“With the economic turmoil today, I understand that the first thing to go in anyone’s budget is usually the art,” Lozano said. “And that goes for individuals, as well as large corporations. That being the case, I make the effort to make sure that if anyone has their heart set on a work of art, and budgets can be of issue, I am open to bartering, arranging payments in a layaway of sorts, trade for services, land, etc.”

“With the economic turmoil today, I understand that the first thing to go in anyone’s budget is usually the art,” Lozano said. “And that goes for individuals, as well as large corporations. That being the case, I make the effort to make sure that if anyone has their heart set on a work of art, and budgets can be of issue, I am open to bartering, arranging payments in a layaway of sorts, trade for services, land, etc.”

Depending on the artist, you also may be required to sign a contract. “It’s very, very important to have contracts because, people being people, their thoughts and circumstances change,” Branch said. “To protect both the artist and commissioner there has to be a contract.”

Branch said she and clients typically agree on a “reasonable price for sketches of the idea, after which point the commissioners would choose one sketch or idea over another, and … they’re ready to say, ‘Yes, this is what I want. How soon can you do it? How much?’ … That’s the point that I would write the contract.”

Branch said her contracts spell out the final cost and the time and payment schedules.

Poteet said she generally doesn’t use contracts. “If I don’t know the person, I will ask for a deposit and then usually halfway through the job, I will send them [a photo of] the work in progress, to make sure we’re both on the same page.”

Lozano said he “usually” uses a contract and that it “works out better that way,” especially when dealing with people from out of the state or country.

Creed, on the other hand, said he always uses contracts. “I always have a contract with the person, especially when we get to making the piece,” he said. “The design fee is generally a contract unto itself. Once I understand what they want, I come up with a design fee that I feel is appropriate and we agree on that, and we proceed.

“The actual building and making of the piece is a different fee. If people are not willing to pay for a design fee, we probably shouldn’t go any further than that. If they aren’t willing to go that far, they aren’t willing to pay for what will arguably be an expensive, one-of-a-kind piece of furniture.”

When asked if an email exchange could suffice in certain situations, like my experience with the folk artist where about $100 changed hands, Creed said it could. “Certainly, some sort of agreement on paper is a very worthwhile thing,” he said.

“It doesn’t have to be filled with legalese. ‘I’m going to do this for you for this amount and this is the date you can expect it by.’ The basics, just a way of keeping everybody on the same page, quite literally.”

Relationships are built when clients and artists work together. Hiring an artist to express your original idea into art will leave both parties with a rewarding experience.